The most powerful man in boxing and the former mutual fund manager who delivered him more than $425 million in institutional capital share a chuckle when they think back to the meeting that started them down the path to prime time on NBC.

Al Haymon had a big, bold and unprecedented idea to bring the sport that once minted icons back into mainstream conversation.

Already the manager of about 50 fighters including Floyd Mayweather, Haymon was on his way to more than tripling his stable, creating enough heft that he could put together a steady stream of credible matchups in most weight classes.

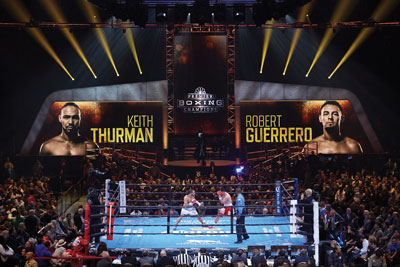

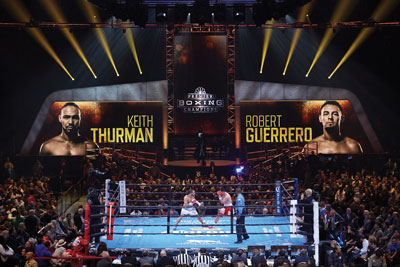

|

The series has invested about $2 million on lighting and elaborate visuals to put on a show that mirrors its grand ambitions.

Photo by: Suzanne Teresa |

But that was only the start of his plan.

Haymon wanted to match those fighters under a consistent, singular brand that would distinguish them from the hodgepodge of boxing scattered across the television grid. And he wanted to do it on the broadly distributed networks that sports fans turn to for the NFL, NBA, NHL and Major League Baseball, most of which had abandoned the sport more than 20 years ago.

So it was that Haymon, his longtime attorney Mike Ring and Waddell & Reed fund manager Ryan Caldwell found themselves across from NBC Sports Chairman Mark Lazarus and Jon Miller, president of programming, late in 2013, discussing a plan that would showcase Haymon’s fighters on the network on weekend afternoons and Saturday nights.

NBC was more likely to shear the feathers from its peacock than it was to pay for a boxing series. But Haymon wasn’t suggesting a rights fee. Instead, it was Haymon who was willing to write a sizable check to NBC. But he wanted more than the traditional time-buy, where the network would take his money and wish him well.

Haymon wanted NBC Sports to not only air his series, eventually to be labeled Premier Boxing Champions, but to bless it. He wanted it produced by NBC, using front-line talent, with features and vignettes like those that are the hallmark of its Olympics coverage. He wanted the network to help promote the series across its assets.

And he wanted the best fights he could make to air in prime time.

It was an audacious request. And an expensive one.

This is why Haymon brought Caldwell.

As he laid out his plan, which would include not only NBC but other broadly distributed networks, it became clear that Haymon’s company might have to bleed upward of $100 million — and perhaps two or three times that much — as it built a brand and an audience, a proof-of-concept phase that would then enable him to cash in on the rights fees that continue to trend upward across sports.

Caldwell was there to show NBC that Haymon Boxing had the wherewithal to not only launch the PBC, but sustain

|

The March 7 series debut, featuring Keith Thurman and Robert Guerrero, attracted more than 4 million viewers to NBC.

Photo by: Suzanne Teresa |

it, with the pledge of upward of $425 million from a $40 billion fund that he co-managed for Waddell & Reed, the same fund that had invested about $1.5 billion in Formula One.

For all that Haymon brought to the meeting in terms of vision, it was Caldwell who had what NBC needed to see that day.

“We laugh about it today,” said Caldwell, who eventually left Waddell & Reed to join Haymon as chief operating officer of the PBC. “Here is Al, who is legitimately successful multiple times over, the most powerful guy in the sport by a long shot, and the only thing they cared about initially was: Is the money real? That was where it all had to start.

“Putting the peacock up for this was a really, really big deal. So I was there to say: Here is our investment case.

Here is why Waddell is behind this and involved.”

The idea and funding behind the most important development to hit the boxing business since in-home pay-per-view have remained largely a mystery around the sport, mostly because the man behind it won’t discuss them publicly.

Haymon, a 59-year-old Harvard Business School graduate who built a successful concert promotion business that eventually included most of the major tours in R&B, does not grant interviews.

With Haymon’s approval, however, Caldwell and Reed agreed to discuss the venture with SportsBusiness Journal, but declined to reveal financials. The investment detailed in this story came from the most recent quarterly portfolio list of the fund Caldwell co-managed, Ivy Asset Strategy Fund, which included among its holdings an investment that those familiar with the deal confirmed was Haymon Boxing: Media Group Holdings LLC, Series H.

Ivy Asset Strategy’s holdings list included a $371.3 million investment in the company. A second Waddell fund, WRA Asset Strategy, listed an investment of $42.2 million. A third fund, Ivy Funds VIP Asset Strategy, showed holdings of $18.5 million. Together they invested $432 million. It is likely other funds run by Waddell also have invested, a source familiar with fund management said, although their positions likely would be smaller.

Between the deep-pocketed funding source, the accumulation of compelling fighters and the willingness to present the sport in a fresh way and market it in a consistent manner, Lazarus and Miller saw enough to consider exploring the matter further.

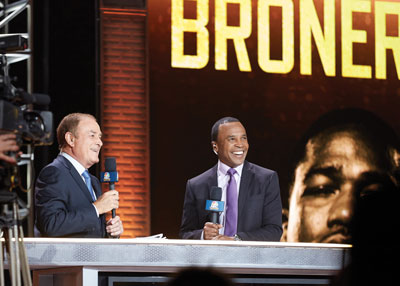

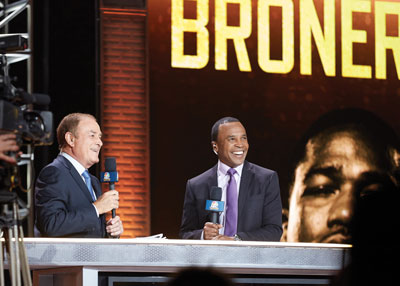

|

NBC bolstered the big-event feel by using Al Michaels and Suger Ray Leonard.

Photo by: Suzanne Teresa |

Eventually, they reached a complex two-year agreement in which Haymon would pay handsomely for air time but NBC would invest as well, paying for some of the production costs, delivering Al Michaels, Marv Albert and Sugar Ray Leonard as on-air talent, and providing promotional assets.

Not long after that, the other TV dominos began to fall: a deal with CBS and Showtime to deliver even more major network exposure, with Spike to reach males 18-34, with ESPN/ABC to cement credibility with avid sports fans and with BounceTV to reach African-Americans.

The PBC’s debut telecast on NBC, a prime-time show headlined by Keith Thurman defeating Robert Guerrero in Las Vegas on the first weekend in March, averaged 4 million viewers during the main event, making it the largest U.S. audience for the sport since 1998 and, more importantly, winning Saturday night for NBC among viewers 18-49.

The second PBC on NBC telecast, featuring Danny Garcia’s victory against Lamont Peterson in Brooklyn on April 11, saw the main event average fall to 3.3 million but again deliver Saturday night for NBC among 18-49s, even though Fox’s prime-time NASCAR telecast drew a larger overall audience.

In between, the PBC debuted on Spike on a Friday night with a main event average of 989,000 viewers and on CBS on a Saturday afternoon with a main event average of 1.64 million viewers.

To put that in perspective, in only four tries, the PBC produced the three most watched boxing telecasts of the last 12 months, with one of them more than doubling the audience for the most watched fight on premium cable leader HBO and the other tripling it.

On the morning of the PBC’s debut show, Ring and Caldwell sat side by side in a meeting room in the bowels of the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, explaining the creation of the PBC and Haymon’s road map for its future.

“An entire world of boxing has been built on short money,” said Ring, who has worked alongside Haymon for 15 years. “What can I get out of this fight and what can I get for a couple of weeks after that? And no one ever looked past it. Because when you look past it, it’s daunting. It’s a daunting investment. But when you get past short to medium to long money, it gets exciting.

“Real exciting.”

Finding the dollars

Haymon has a wealth of experience and deep connections that reach to the top of major networks and entertainment companies. But he operates as the consummate entrepreneur, working mostly on his own, often while on the move, an old-school flip-phone pressed to his ear. He doesn’t use email and prefers talking to texting.

With the PBC, he came to the realization that he’d need more of an infrastructure, in part at the urging of his investors. Early on, Caldwell told Ring that the fund would invest only if he left his law practice to join the business full time as Haymon’s chief of staff.

“Not only did Al know this was going to be hard to pull off, but he was going to for the first time have a capital partner,” Ring said. “I don’t think the man has ever had a loan, never mind an investor.”

While Waddell could hold a seat on the board of directors and give advice, Caldwell was precluded from taking an active role in management. But he had a wealth of ideas, including a logical build-out of the business that would start with two of the assets over which they had the most control — digital and social — and then move quickly to securing TV deals.

Caldwell’s introduction to the value of sports rights came in 2009, when Waddell & Reed’s Ivy Asset Strategy Fund was on its way to becoming the largest institutional investor in CBS.

CBS stock was decimated at the time, but CEO Les Moonves was telling anyone who would listen that the market had it all wrong, that the company was on its way to bolstering profits as it moved toward using its more popular content as leverage to collect larger retransmission fees from distributors.

Time and again, CBS went into carriage negotiations threatening to pull its local affiliates from the grid if the cable operator didn’t pay more. Time and again, often at the 11th hour, the provider caved.

Caldwell couldn’t help noticing that that deadline frequently coincided with the start of the NFL season.

“What was driving retrans? Live sports,” Caldwell said. “So as the investor, you say, wait a minute. Being the distributor of live sports is nice. But I’d really like to own live sports. That’s the driver from an investment standpoint. As brilliant as Les is, if you don’t have the NFL as a hammer, you can’t do what he did.”

|

Danny Garcia enters before his fight with Lamont Peterson as the series visits Brooklyn’s Barclays Center on April 11. The fight on NBC attracted 3.34 million viewers.

Photo by: Getty Images |

Caldwell filed the observation for another day. It came in the middle of 2011, when a banker associate from UBS called with an opportunity.

“You guys like this media stuff,” he said. “I’ve got a weird one for you. But I think you ought to take a look.”

Caldwell agreed to listen to a pitch from private equity firm CVC Capital, which was shopping a stake in Formula One. The fund took a position, along with a seat on the F1 board. From that vantage point, Caldwell learned the sports landscape. Again, he was struck by the ability to leverage rights and lock in costs over a span of years.

Caldwell and his associates at Waddell began trolling for more investments in sports. They talked to the UFC about a minority stake, but it had already sold shares to the Abu Dhabi government. They looked at major pro teams but weren’t sure about the match between an institutional investor and a league.

In 2013, the sports opportunity found them.

Caldwell got a call from Thomas Tull, chairman and CEO of Legendary Pictures, a company in which Waddell & Reed held a 20 percent stake worth about $450 million. A lifelong Pittsburgh Steelers fan who owns a minority stake the franchise, Tull wanted to set up a meeting for him with Ring, who was a mutual friend.

“We’d like to talk to you about something interesting,” Tull said.

“What’s that?” Caldwell asked.

There was a pause.

“Don’t throw up,” Tull said. “It’s the sport of boxing.”

Caldwell was a longtime fan, so he didn’t have the aversion Tull expected.

“It’s with Al Haymon,” Tull said.

“I don’t believe you,” Caldwell said.

“You know who Al Haymon is?”

“Of course I do. I told you, I follow boxing. I know who Al Haymon is. And I know Al Haymon is not going to sit down and talk to me.”

“No,” Tull said. “We’re going to put together a meeting.”

Caldwell agreed.

Their first sit-down was at Tull’s studio office in Burbank, Calif. Caldwell couldn’t make the trip but called in.

Haymon started off with his vision, speaking passionately about how decades of narrowing distribution had eroded interest in a once-popular sport, moving the stars first to premium cable and then to pay-per-view. The model had been good to Mayweather, a Haymon client who emerged as the world’s highest-paid athlete. But for the broader class of fighters, the path had narrowed to the point that it was difficult to break through.

Ring and Tull listened as Caldwell asked questions and he and Haymon parried ideas.

“Al had been thinking about this for years,” Ring said. “He’d just never thought, from a business perspective, that you could actually go out and get money to do it.”

Soon after their conversation, Caldwell contacted associates from CVC, the London-based private equity firm that introduced Waddell to F1. He remembered that early in 2012, CVC had kicked the tires on a boxing investment, looking into the purchase of Golden Boy Promotions.

CVC representatives made an exploratory trip to the U.S. but went home without a deal. When Caldwell asked why, they said that they didn’t see the profits they had expected, largely because the bulk of the revenue generated by the fights went to the fighters, especially in the big pay-per-view bouts headlined by Mayweather.

It was a shift in the economic model brought on by Haymon, who negotiated deals that put the revenue from an event in the hands of the fighters, paying promoters a fee rather than giving them a cut. In the music business, Haymon learned that the leverage belonged to the headliner. He thought the same should be the case in boxing.

As Caldwell considered the investment in Haymon’s idea, he saw that shift as an advantage. If Haymon had management deals with a critical mass of fighters, he was the one with the best chance to turn that into a lucrative rights deal. In boxing, there was no team or league or racing circuit with consolidated rights for Waddell & Reed to invest in. Haymon would have to create it.

While Caldwell would not discuss funding specifically, he said that Waddell & Reed invested considerably more than Haymon requested in the initial business plan.

“Al said, ‘I think I can pull this off for x,’” Caldwell said. “And I turned around and said ‘Absolutely not. It’s x-plus or we don’t do it.’ You have to be capitalized for three to five years to do this. To weather the storm. Because in some regards you were going to be the irrational player for a while.

“You’re turning the model completely upside down.”

Caldwell framed his case to the fund’s board in Wall Street terms: An undervalued call option, with the high risk but high return. They would put about 1 percent of the $40 billion fund into Haymon’s venture, prepared to lose all of it.

Waddell & Reed would marry its capital to Haymon’s management contracts. Revenue would come from the 15 percent that Haymon’s company received from fighter earnings, typically beginning only after the fighter has begun to earn purses of $100,000 or more.

In boxing, purses are based on shares of revenue from the fight. A look inside the financials of the PBC’s debut card reveals the money the company must bleed while it tries to earn its way to the table for a rights discussion.

According to payment sheets filed with the Nevada State Athletic Commission, the four fighters who appeared on the main card on NBC received a combined $4.425 million, with headliners Thurman and Guererro getting $1.5 million and $1.225 million, respectively, and opening fight star Adrien Broner getting $1.25 million.

Not all cards will carry as hefty a payout as the NBC and CBS shows, but even the Spike menu carried a seven-figure price tag: $1.25 million in purses for the main event featuring Andre Berto and $650,000 for the co-feature, according to documents filed with the California State Athletic Commission.

Typically, the majority of the revenue to pay those purses would come from television rights bought by HBO or

|

Dana Jacobson and Thomas “Hitman” Hearns cover the action for Spike on March 13. The card in Ontario, Calif., was the first appearance for the series on the network.

Photo by: Getty Images |

Showtime, supplemented by sales of tickets, sponsorships and foreign TV. The PBC debut card at the MGM Grand brought in $1,036,050 on sales of 9,806 tickets ranging in price from $25 to $400, according to NSAC ticket tax filings, with 6,126 of those priced at $50 and 1,225 priced at $100. The Spike card at Citizens Business Bank Arena in Ontario, Calif., sold 5,842 tickets worth $245,092 in revenue, according to CSAC filings.

Because federal law prohibits managers of fighters to also promote fights, the PBC will work with a handful of promoters, most of them tied regionally, paying them a fee to operate the shows.

While they will execute the events, there is no question of who will make most of the decisions with regard to matters such as ticket prices and presentation. The latter of those is a core matter for the PBC, which spent millions to build a massive, state-of-the-art stage and center-hung video board that it will take on the road for all of its

events, scaling it up or down to match the size of the venue.

After the PBC event in Brooklyn, Barclays Center CEO Brett Yormark was struck by how many people said they saw him ringside at the event, including many who don’t follow boxing but were drawn to the broadcast by its apparent scale.

“You walk into the building or turn on NBC, you see the stage and the lights and all the things they’ve done, and it feels like at a big event,” said Yormark, who hopes to host as many as six PBC events a year, with Amir Kahn on May 29 announced last week. “That’s the business I want to be in. That could be a transformational step for boxing.”

The PBC has invested in boxing as no promoter, manager or network ever has.

In its first year, it is scheduled to put on as many as 42 events, about the same number as the UFC. Haymon isn’t necessarily following the playbook that got the UFC from a pay-for-air property on Spike to a rights fee on that network and then an even larger one from Fox. For one thing, the UFC was introducing a sport. The PBC is merely trying to revive one.

UFC executives have said they were surprised at how aggressively the PBC launched, with an ambitious schedule spread across so many outlets.

“This is the thing we’re incredibly self-aware of,” Caldwell said. “We do not think that this is easy; that we show up and all of a sudden there’s ratings and those ratings are representative of advertising rack rates, and all of a sudden the world is a cheery place. We didn’t capitalize the company based on that.

“What we anticipated was this: We think there’s a latent boxing audience that is unreached by the current distribution system. We think if we expose the sport and the kids and their stories to that audience we can immediately have a bigger fan base than exists in the sport today because it is underserved. We think there’s a demo overlay that fits on top of those … fans that advertisers would love to get to as the face of this country continues to look different over the next 10 years.

“We think we have that. Now, we have to prove it out.”

NBC buys in

The president of programming for NBC Sports stood at floor level of the MGM Grand Garden Arena, looking up toward a 75-foot-wide stage as the fighters made their way to the scales for weigh-ins the day before the PBC’s inaugural event in March.

Miller flashed back almost 30 years ago, to the last time NBC aired a fight in prime time: Larry Holmes defending his heavyweight championship against Carl “The Truth” Williams on a Monday night. Miller was a rising salesman at the network.

“We did a lot of business,” Miller said, looking skyward at a massive screen above the ring that aired NBC Sports Network’s live coverage of the weigh-in. “Budweiser bought the fight. GM bought it. It was a different time. People knew Larry Holmes was the heavyweight champion. And that meant something.”

It wouldn’t be long before that era of boxing was laid to rest. Many of the stars of the sport migrated to premium cable. Network ratings declined. Advertiser support dwindled. CBS, NBC and Fox took intermittent shots at the sport, but never with any vigor.

Miller first heard of Haymon’s idea to bring boxing back to broadly distributed TV in the fall of 2013, when he ran into Caldwell at the F1 race in Austin, Texas. He was admittedly skeptical. But Caldwell convinced him to hear Haymon out.

At that meeting, Haymon laid out his vision: To revive interest by exposing and then developing stars using broadly distributed television, presented in a unified manner under a single brand, similarly to the NFL or NBA.

Miller and Lazarus listened, then laid out all the roadblocks. With no established ratings history, it would be impossible to attract advertisers. In order to attract viewers, you’d have to get premium-cable-quality fighters, who would be prohibitively expensive. The last time boxing was on the networks, it was driven off in part because the product was so bad. There was no reason to believe this would be any different.

“We threw up all the reasons why it wouldn’t work,” Miller said. “And they deftly dealt with every question. Their plans, while ambitious, were really well thought out and very reasoned.”

When Miller returned to New York, he checked into Haymon’s stable and found it was deeper in both quantity and quality than he expected. He checked with others he respected, including former HBO Sports head Ross Greenburg, all of whom spoke highly of Haymon’s capacity to deliver quality fights.

Miller went back to the PBC to fine-tune a plan. Then he went to Los Angeles to present it to NBC’s entertainment division, pitching it on the idea of freeing up prime time on Saturday night —- not so tough a sell because the network has gotten killed there for years. Miller had to convince them he could do better than what they already had, making the pitch that a show like the PBC — which might initially attract an older audience — could serve as a strong lead-in to local news and then “Saturday Night Live.”

It looked cost-effective enough to make it worth the risk.

Once NBC was on board, Haymon began clicking off the rest of the puzzle with deals with the other networks, each of them tweaked slightly to match their needs.

To be clear, this would not have happened had Haymon started off by asking NBC to pay for it all. But it is not as simple as a $20 million time-buy on that network that has been widely reported, according to executives from both sides.

The PBC is collecting some rights fees. It also is paying for some air time. The main reason the deal had to be structured similarly to a time-buy is that it was the most logical way for the PBC to create sponsorship and advertising inventory across so many networks.

“It’s not a time-buy,” Miller said. “The reason we’re not selling it is because you couldn’t have six different networks out there selling the same product — and certainly not a product without a track record. So you have one group selling everything. And that’s really the brilliance of the concept.”

This, the PBC believes, will be a key differentiator for it as it navigates the sponsorship and advertising landscape that eventually will determine whether it survives.

To approach the broader sports sponsorship community, the PBC hired SJX Partners, the agency headed by former U.S. Tennis Association executive Harlan Stone, to create integrated packages that include spots during fights, branding on the ring, digital assets, tickets and hospitality, a package rare in boxing because it has been off advertiser-supported TV for so long.

The PBC also brought in Bruce Binkow, the former chief operating officer of Golden Boy Promotions, to advise it on operational matters and also to maintain relationships with brands already in the sport, such as Corona, which thus far has been the only sponsor visible at PBC events. The PBC is far along in discussions to make the brand its first series sponsor, sources said.

The way the PBC sees itself — as the irrational player willing to bleed money to prove its theory and then cash in on it — is precisely the way that boxing’s incumbent players perceive it, save perhaps for the confidence that the brand bomb will yield a return on investment.

“We feel like other television networks getting into boxing and broadening awareness of the sport is all going to rebound to HBO’s benefit and is a good thing,” said Ken Hershman, president of HBO Sports, which for the last two decades has attracted the largest ratings for boxing. “The jury is still out on whether financially this is going to be a sustainable business model. That’s up to them and the networks they’re working with.

“I would imagine there will be some level of disruption if the money coming into the system is as significant as it appears to be. I don’t think you can pretend it won’t cause disruption in the marketplace [for TV rights to fights].

How that translates to what we’re doing, time will tell. But if you don’t answer to anybody, don’t have to deliver ratings, and have a war chest to keep doing things, there’s no question it can be disruptive to typical operation of the system.”